- Preview

- Stages 1-9

- Stages 10-15

- Stages 16-21

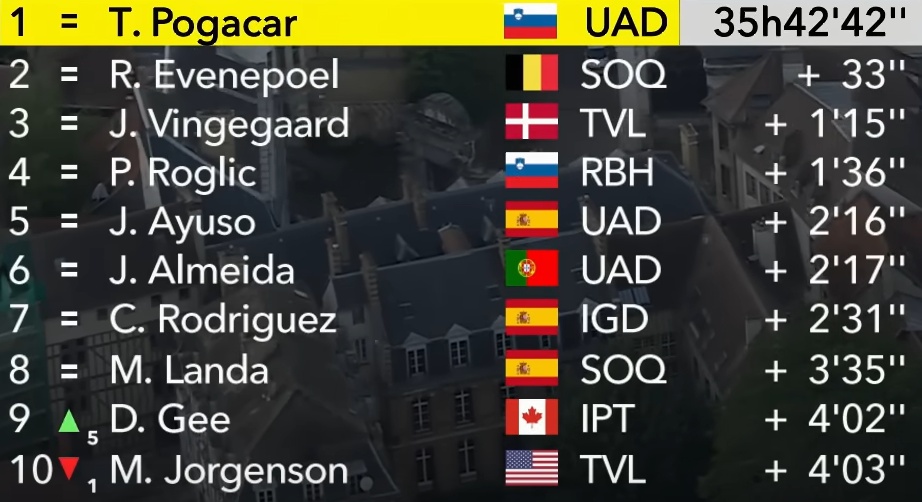

After nine stages of the 2024 Tour de France, the big stories are probably Remco Evenepoel inserting himself between yellow jersey Tadej Pogacar and reigning champion Jonas Vingegaard, and Mark Cavendish winning a stage – a feat that is almost paradoxically newsworthy precisely because of what a common occurrence it has been.

Roll up, roll up… and then roll up another five times after that

As flagged in the preview, this Tour de France didn’t ease the riders in this year. Stage 1 was a hilly-to-mountainous beast of an opener with seven categorised climbs. Given the way it went, we can expect this trend for challenging starts to continue in coming years.

The literal result was that Romain Bardet finished 5s ahead of the peloton to secure his first yellow jersey in his final Tour.

However, everyone who saw this stage knows that VDB was the MVP – a truth quite beautifully illustrated by Bardet’s ‘victory’ celebration.

With about 50km to go, Bardet exited the peloton and made his way up to the remains of the day’s break. There he linked up with young team-mate Frank van den Broek, riding his first ever Tour.

Bardet had every right to be fresher than the men he’d caught and duly dropped them all, except for van den Broek.

The idea then was that the Dutchman would contribute whatever he could until he could do no more to give Bardet the best chance of staying away from the peloton.

It’s a pretty standard plan in these situations, except van den Broek managed to stay with Bardet until the end and in fact looked the stronger of the two for much of the ride, despite having been out in the break all day.

If a two-minute advantage is down to five seconds at the line, the guy who helped you just about stay away while willingly accepting second place is the real hero. The image above suggests Bardet agrees.

Plus ca change

Stage 2 was another nasty one for an opening weekend, featuring two ascents of the short, mad bollocks of a climb up to the Basilica San Luca in Bologna.

Tadej Pogacar doesn’t need a steep climb to encourage him to attack, so finding himself on one he couldn’t resist.

Jonas Vingegaard was the only rider immediately capable of following him, so, on the face of it… here we were again.

It’s a long race though and there are valid reasons (Giro fatigue, stunted preparation) to believe either or both of them might fade in a week or so. It was also noteworthy that Remco Evenepoel – essentially riding alone with a Richard Carapaz shaped trailer – managed to power across to them before they reached the finish.

Rise and fall

For all that Pogacar’s Stage 2 attack had been too much for everyone bar Vingegaard, it was really no more than a minor skirmish. After a sprint win for Biniam Girmay (Eritrea’s first Tour stage win) on Stage 3, we entered the mountains proper on Stage 4. (Girmay would later notch Eritrea’s second Tour stage win on Stage 8.)

The mighty (it’s always ‘mighty’ for some reason) Galibier tops out at 2,642m and while the thinness of the air at that altitude will have affected plenty of riders, the second category slog to Sestrieres earlier in the day will have had a pretty big impact too, I’d wager. An average gradient of 3.7% is barely worth remarking on for these riders, but sustained for 39.9km it’ll certainly have sapped some energy.

Pogacar was, again, the man to attack near the top of the Galibier. Vingegaard was, again, the only man who could follow him… until he couldn’t.

A handful of seconds’ gap over the top eventually expanded as the long descent wore on.

By the finish, Pogacar had gained 35s, plus some time bonuses. At this point the intrigue was arguably already shifting into the final week when the Slovenian’s Giro d’Italia efforts could, theoretically, start to catch up with him. (At least there is some intrigue…)

Remco Evenepoel, Primoz Roglic and Carlos Rodriguez all caught Vingegaard on the descent, as did Pogacar’s team-mate Juan Ayuso, meaning there are still a few names in the mix in the event the two favourites fade or crash or get covid.

The other guy

After a sprint stage won by someone who isn’t Mark Cavendish (Dylan Groenewegen, armed with a bizarre aero nose cover thing), it was the first of this race’s two time trials. It’s worth emphasising that the second one comes on the final day, which means time trial form becomes doubly intriguing.

That said, there is not much to say about time trials beyond the bare result.

Remco Evenepoel was quickest.

This wasn’t really a colossal surprise given that he is the world champion in this discipline. At the same time, Pogacar and Vingegaard habitually save their best time trialling performances for the Tour de France and even when others have gone close to them in the past, they haven’t tended to be overall contenders.

Remco is different. Despite his weaknesses (not quite their equal on the long climbs and prone to (quite understandable) nervousness going downhill) he is at this point a genuine threat to both riders, and in fact sits ahead of Vingegaard in the general classification at the end of this first week.

Jonas’s gravel ball shortfall

I said in my race preview that Evenepoel was unafraid to speak his mind. He duly had this to say about one of those rivals in the wake of Stage 9’s gravel carnage.

“We have to accept race tactics and race situations, but sometimes you also need the balls to race. Unfortunately maybe Jonas didn’t have them today.”

The Belgian’s complaint was that on a day when the overall contenders started trading attacks with 100km still to go, Vingegaard declined to work with himself and Pogacar when there was an opportunity to distance the rest of the top 10.

Vingegaard’s view was that the gravel stage was a bloody nightmare and he was more than happy to emerge from it with no meaningful changes to the general classification (unless you count Derek Gee moving up to ninth as meaningful, which you almost certainly don’t).

Just as a measure of how chaotic the gravel sectors were, riders further back were reduced to walking up one of them.

Vingegaard’s muted ambition to simply hang in there may have disappointed Evenepoel, but it was perfectly understandable. This was not his thing and he has not arrived at the race in perfect condition.

If the Dane can arrive in the mountains late in the race as fresh or fresher than his two main rivals, this is where he has won the last two Tours de France. Maybe then he can invite Remco to do a quick testicle tally.

Cav’s week

Mark Cavendish vomited his way through the heat on Stage 1, surrendering 39 minutes and also a certain amount of optimism about his chances of edging ahead of Eddy Merckx when it comes to stage wins.

Cavendish would be the greatest sprinter the sport’s ever seen even if he’d chundered to a standstill and abandoned on that first day. At the same time, a large part of what got him to 34 stage wins was his commitment to getting through these kinds of horror days.

Stage 2 looked a bit of a slog for him too, so the odds were against victory on Stage 3 even before he was held up by a crash. However, after cresting the Stage 4 mountains, the flatter roads of Stages 5, 6 and 8 hoved invitingly into view and he notched that 35th win at the first opportunity in inexplicably familiar style – inexplicable simply because it’s so unlikely he should still be doing this; threading his way through his rivals and crossing the line first.

The actual sprinting is probably the least impressive aspect of his feat (most stage wins at the Tour de France). We already knew Cav was the finest sprinter there’s been, even if there’s a new dimension in still delivering at the age of 39.

More impressive is the commitment and determination; the simple refusal to give up in the face of overwhelming odds. Chucking up and labouring to the finish on Stage 1 was only really a very small display of that.

In 2017, Cavendish was diagnosed with Epstein-Barr virus and couldn’t race for a few months. On Stage 4 of that year’s Tour de France, he found minimal give in Peter Sagan’s elbow during a sprint finish and suffered a fractured shoulder blade.

The following year began with a series of crashes and a single stage win at the Dubai Tour. This proved to be his last victory of any kind until 2021.

To put that in context, Cavendish had hit double figures for victories every year since 2007. He had won 23 races in 2009 alone. Now here he was in his mid-30s with one win in 2017, one win in 2018 and zero in 2019 and 2020.

If there is a defining moment from this period, it was when he missed the time cut on Stage 11 of the 2018 Tour but rode to the finish anyway. That is the moment I have thought about most since he went past Merckx.

They were clearing the barriers away when he arrived. The podium ceremonies were done and dusted.

While he later found out that his Epstein-Barr had returned and that he had ridden with it for months, there’s no handicapping system in road racing. Cavendish’s results weren’t going to be upgraded because he had a virus. This was a bad – surely terminal – situation for a mid-30s sportsman and it was no grave miscarriage of justice that his team didn’t pick him for the 2019 Tour.

Changing team didn’t much help. He missed the 2020 Tour as well and towards the end of that season he was wondering out loud whether this was the end.

Then he signed for Deceuninck-Quick Step on the sport’s minimum wage – and only then on the proviso that he also brought in a sponsor. Having gone 1,159 days without a victory, he won a stage at The Tour of Turkey. Then he won the next day. And then again the day after that.

A little later in the season, he won four stages at the Tour de France to draw level with Eddy Merckx, who paid tribute thus: “I haven’t seen him in a long time, but in his first period with Quick-Step Mark Cavendish sometimes slept at my home, with some other riders, during the criteriums. Mark was the only one who cleaned his room and left it neat and tidy.”

Merckx doesn’t give you much.

It’s worth underlining that, in fact, because while Cavendish has edged ahead of Merckx on stage wins, the Belgian is still five overall Tour de France victories clear of him. (He also managed all of this in a span of just seven years.)

But that’s part of the story really. Merckx spread his 34 victories over flat days, hilly days, mountain days and time trials. The fact that Cavendish has gone past him from bunch sprints alone is not just testament to his peerlessness in that field, but now also to his sheer longevity and unimaginable resilience.

Because really, even those 2021 wins are a while ago now. In 2022, he sat out the race again and then last year he crashed out. Even his profoundly unlikely Indian summer is now three years in the past.

Time unavoidably moves on.

But then somehow, next thing you know… there’s Cav winning a Tour de France sprint stage again.

What’s next?

I have a buy me a coffee/Belgian beer page if you’d like to thank me for writing a week one recap that was honestly far too long. (And yes, I do promise all contributions will go towards one of those two things. I also promise the next two recaps will be shorter.)

A quick word for new readers at this point too: You can (and should) sign up to receive these recaps by email. I’d also really appreciate it if you could please recommend these emails to someone (anyone) as I cannot be bothered marketing the site myself.

When it comes to the next batch of racing, week two is kind of half-and-half with sprint stages on Tuesday, Thursday and Friday.

Stage 11 (Wednesday) has a good few smaller climbs towards the finish and while it’s most likely a day for the break, the overall contenders might get sucked into a few efforts.

Stage 14 (Saturday) is a summit finish after earlier going over the Tourmalet (19km at 7.4%)

Stage 15 (Sunday) is Bastille Day, so obviously it’s a big ‘un: 4,800m of climbing over 198km, finishing atop the Plateau de Beille (15.8km at 7.9%).

As ever, I’ll try to get a recap out on the next rest day or, if other commitments prevent that, not too long afterwards.

Leave a Reply